In the early years of the twentieth century, the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, who had previously focused on impressionist presentations of landscapes, was moving in a more abstract direction. Moving from the Netherlands to Paris in 1911, he was visiting his home country upon the outbreak of World War One, which made returning to Paris somewhat difficult. Already influenced by the new art style of cubism, Mondrian’s stay at the artist colony at Laren during the war allowed him to met other artists, such as Bart Van der Leck and Theo van Doesburg. The three artists, all moving towards abstract art, collaboratively began an art movement named De Stijl, or “The Style”, with a journal by the same name publishing essays on the movement and its theory of art, which Mondrian called “Neoplasticism”.

Continue reading8 of Hearts: 2022 Games of the Month 1: Praey For The Gods

Praey For The Gods is in some ways an extremely easy game to talk about. It is a Shadow Of The Colossus-like, a game where you find huge creatures scattered around the map at the direction of mysterious, disembodied spirits, climb to weak points spread around their bodies and slowly bring them down. Added on top of this is a winter themed survival system which mainly comes into play in the spaces between , which, with the breakable weapons, warmth mechanics, gathering mystical items to exchange in groups for either health or stamina, and a handheld glider for easy vertical movement, feels mainly based on The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild. As a final small comparison, the somewhat sparse writing often has the cadence and feel, if not delivery method, of a Dark Souls game: the opening narration talks about a dying world ending with a repeated refrain of “Ring The Bells”, which immediately put me in mind of “Link The Flame” as a short, three word mission statement for your aims in the game.

I don’t think these comparisons to other games are unjustified. The similarities to Colossus in particular are so striking it is genuinely hard not to talk about the game in those terms, defining it primarily by how it follows or deviates from a now seventeen year old game, but I feel like I want to avoid doing so too much. Partially that’s just due to me wanting to try and flex at least some review muscles and not take the easiest route, and partially because I feel the game has at least earnt being examined on its own, merits and flaws alike. In many ways, it is an extremely impressive game, considering it was developed by No Matter Studios, a three person team. Initially developed part time, they were able to switch to full time following a successful 2015 kickstarter campaign that netted them $300,000, twice their initial aim. The game was first released in 2019 as an early access title on Steam, with the full version released in December 2021, making it eligible for the January slot of these reviews. (For reference, the curious spelling is due to Zenimax protesting No Matter Studios filling as Prey for the Gods as Zenimax argued it was too close to the game Prey. No Matter Studios, not wanting to go up against such a big company, changed the name)

The game’s biggest strength is its visual design. “Frozen wasteland” is a very easy setting to make visually really boring, giving the player endless identical white and grey vistas to run (or slip on ice, or slowly trudge through snow) across, but the game gets around this by having its environment be primarily vertical. The archipelago of the game’s setting is a well laid out collection of mountains, cliffs and plateaus, taking a limited palette and using it to create an array of visually distinct corridors for you to pass through, while the grappling hook and glider provide easy vertical motion to stop navigating the island from constantly feeling like a literally uphill slog through the snow.

It helps that a lot of the cliffs are, in fact, frozen giants.

These are literally background features: you rarely even find yourself climbing across them before the finale, but as well as breaking up the landscape, having these great icy figures either towering over you or desperately clawing at the bases of cliffs, trying to pull themselves out of the sea establishes the mood of despair, of being a tiny figure in a doomed land surrounded by the shades and bodies of those who came and failed before you, where even the giants who’s shoulders you may stand on are nothing but helplessly frozen wretches themselves. It is a good mood to set for a game like this where, armed with little more than some fragile, cold damaged weapons that cannot even scratch their hides, you must face down monsters once worshipped as gods. The bosses are, themselves, appropriately huge and morbid in design, creatures of bone, fur and stone bound by ropes and chains by those who have come to the islands before you. The appearance of the first boss, the Satyr, rising out of the snow in the first cutscene was what initially sold me on the game enough to complete it, the way a hill becomes a seemingly mobile corpse of a giant, its face ripped back to the bone, swinging desperately at your tiny figure. The bosses are similar enough to be obviously of the same nature, while each having at least some gimmick such as being a huge tower like worm spewing purple lightning at you, a charging boar who you need to stun by tricking it into slamming into a wall, or a giant half dead crow that you desperately cling to as it flaps through the sky. It is all design aesthetics we have seen before, but it is done well, and the game maintains this morbid, frozen, desperate atmosphere through to the beginning of the finale, which…goes places I both expected on one level given some of the obvious inspirations but I did not expect how hard it went.

Unfortunately the game is ultimately let down by its mechanics. I’d never say it drops below the level of mediocre, except for one notable and quite important exception, but the game is trying to do a lot and can’t quite stretch itself out enough to cover all it. The survival mechanics are, on one level, kind of obvious for the themes and atmosphere the game is going for. Having a warmth mechanic makes sense for a game about the end of the world triggered by an endlessly harsh winter, but the implementation is less lacking and more…minimal. There’s no recipes for food that I could find, just cooking and eating the meat and mushrooms you find across the island. The sleep meter rarely comes into play, at least on the default difficulty, as even a small amount of exploring will yield plenty of one use bedrolls to clutter your somewhat small inventory. The warmth mechanic is the closest the game comes to really engaging with these, since it is obviously linked to the state of the world, dropping faster in windstorms than in caves, and being controllable by making fires and upgrading your clothes (refreshingly seriously designed for a female video game character), but it still doesn’t *do* much, outside of the higher levels of the (admittedly impressively broad and clearly defined) difficulty levels. Those upgradable clothes are another example: while you can upgrade them with furs taken from hunt-able animals around the islands, the defence bonuses those upgrades provide are honestly less noticeable than the fairly subtle visual changes each part of the outfit goes through when upgraded. You can even find other clothing sets in treasure caves around the island, protected by puzzles that honestly tend to be impressive and enjoyable enough I wish they were a bigger part of the game, but these medium and heavy clothing sets still don’t feel important enough to really be worth focusing on. Hell, they are even called, in game, light, medium and heavy clothing.

Non-boss combat isn’t really much to talk about. There are very few enemy types, and it is rare to have an encounter with a minor enemy that actually feels interesting. The closest is probably the occasional puzzles where you need to trick tiny versions of the giant worm boss into powering mechanisms for you by standing behind the power conduits, which is less combat and more another puzzle, an area which, again, the game does well in general. The weapons do, of course, break, but the combat encounters are far enough apart and the weapons numerous enough that this was far less of an issue for me than it is in other, similar games. I suspect that in a more mook combat focused experience, the rate of decay would annoy me a lot, but here it is saved by it just not really mattering. The only things you need to keep an eye on is having a good supply of arrows, since they are useful for both some bosses and plenty of puzzles using classic “light torches with flaming arrow rules, and on higher levels, making sure you have a non-broken grappling hook on you at all times, since that is really the only weapon that feeds into the mechanical meat of the game.

Praey for the Gods is a game about climbing. Climbing up mountains so you can leap off them to glide to the bosses and start climbing up them. Vertical movement is key in this game, and while the grappling hook and the glider are pretty well handled, letting you keep a brisk pace up and down the side of cliffs, the core mechanic is climbing. And unfortunately it is probably the worst mechanic in the game. Not due to it requiring stamina: I think that’s a really good idea and fits this kind of boss a lot better than health as a limiter, since “can you keep going and climbing, or will you fall and need to start again” is a far more interesting limitation in a boss fight than “did you die and need to restart the rather long fight entirely”. There are some awkward bits in how the climbing controls in general, it being slow and kind of awkward to leave on command, but it is some specific but extremely common scenarios that cause the system trouble. For one thing, your character’s climbing animation will always point to a global up, and if she finds herself facing downwards, she will reorientiate herself so her head is always above her feet. The problem is you will find yourself climbing the arms, wings and other limbs of the bosses, meaning that you will constantly find your controls adjusting themselves with the movement of the bosses; you might begin climbing straight up along the arm, but then the boss lifts its arm, tilting the surface you are on ninety degrees and suddenly your forward motion is pushing you around the circumference of the wrist.

Even worse, when that boss lifts the arm, you may find your character struggling to hold on. This is hardly unexpected; you are climbing on giant creatures trying to throw you off, there needs to be some kind of mechanic that has you clinging on for dear life, but that mechanic is just spamming right click. It is an extremely boring mechanic, and one that you will find yourself doing a lot. Each boss has a number of metal sigils implanted in their body by the ones who came before you, which you need to reach on the body and ring by pulling out a central metal core and slamming it back in (The “Ring the Bells” action mentioned in the prologue, since doing so creates a bell ringing sound). Each bell takes three goes to ring properly, and both during each pull back and after each successful attack the boss will immediately start trying to throw you off, meaning that you will have to spam right click at least nine times each fight (the bosses having a minimum of three bells on their forms), not counting all the times you will start being thrown off while you are climbing the bosses. It’s a vital mechanic and it is just really badly done.

The individual bosses are impressively visually but are for the most part fairly standard fare mechanically, having a clear weak point you find and exploit to stun them long enough for you to start climbing. The standout for me is the fourth boss, a giant flying ribbon fish which avoids the climbing issue by spending the clambering over the boss stage of the fight either with you running around on its back and not needing to climb, or with you dangling from what is not the bottom as it flips over in midair, a fight that genuinely left me feeling dizzy and finding myself trying to mentally correct the rotation of my twitter feed having spent half an hour guiding a character as the screen’s contents rotates around me. There’s also a rather interesting sudden shift near the end, which I won’t go too far into here but at the seventh boss, which is notably the one that was released with the ending with the full release, the game suddenly introduces a new mechanic which becomes really important for the finale. Seven out of eight bosses is a bit too late to be introducing a vital new mechanic but I can understand why the team did it, given the development history.

The game is ultimately I think just over ambitious, adding too many mechanics in and not really polishing the core mechanics for the gameplay it is going for. With the exception of the climbing, nothing is done badly, but a lot of it is just the bare minimum in scope, reasonably competently executed. I feel like it would have been drastically been improved by a bit of focus, cutting some of the extra mechanics (I could do without the sleep mechanics at minimum even if the game kept the other survival meters) and really nailing the core boss climbing game play.

Alternatively, that focus could go into fleshing out the writing. While you do find notes scattered around the island, I finished the game honestly confused as to exactly why I was doing this. There’s some vague talk from three dead ladies you find under a shrine about it being a route full of sacrifices, and you can definitely make some conclusions with some fairly basic knowledge of norse mythology, but it did leave me wanting just a bit more actual text. Not explaining everything but explaining something, at least. As far as I can tell there wasn’t any really lore relevant to that in the notes scattered around the island, which tend to either be from one particular guy who also does not seem to know what’s going on and is very worried about this (and which, to be fair, does explain the state of the island as you find it), or function mainly as hints for the bosses or treasure locations. The writing is, for the most part, fairly average. Not bad, but not standing out particularly either.

Praey For The Gods is, ultimately, a reasonably serviceable game that, like the frozen giants it displays, is trapped while reaching for better things. It is an impressive feat for the number of people working on it, but its lack of polish drags it down. I did play through the whole game before writing this, which I think should be taken as an important indication that it is definitely not bad, and some bits are really enjoyable, but it is not at all everything it could be. Currently it is on sale on Steam for £25, which I feel might be a bit much, but if you enjoy Norse mythology and boss climbing gameplay, you might want to pick it up maybe a slight discount. If you don’t already know you like the look of the game however, I’d leave this one.

Honestly if you have access to a playstation console I’d say you might want to just go get a rerelease of Shadow of The Colossus. I know I said I wasn’t gonna bring it up but it’s still true.

5 Of Diamonds: Randomness in Art (A Potential Starter)

(I’ve had like 5 posts staring at me from the back burner for weeks now. Let’s see if I can get any kind of momentum rolling with some shorter posts. These potential starters are going to be thoughts I’ve had floating around recently. Research will be minimal, as the point is to document a starting point of my understanding of a topic that I haven’t had a chance to look at in detail).

This is Squares Arranged According To The Laws Of Chance, a dadaist collage created by Jean Arp in 1917. It is the first of his chance collages, created by ripping coloured paper pieces into rough shapes and then dropping them from a height onto the backing, pasting them where they land to create a unique composition for the collage.

I’ve often used randomness as a prompt to begin a piece of art, mostly writing, to give myself something to go on rather than just a blank page, such as characters created from a couple of given traits, stories based in a particular genre that must include particular words, or even just constructing Jojo Stands by hitting random on the Superpowers wiki and a list of songs or album. Sometimes I use randomness in the opposite way, filling in details of characters or settings that don’t really matter for the role they are filling in the story, usually gender or ethnicity since my attempts at writing tend not to approach these directly. I guess you could also argue that roleplays are a collective story telling exercise which are steered by a degree of randomness from dice roles?

Actually yeah I think I am going to argue that, so throw roleplays and gamified story telling in general on that pile. [Entirely unrelated note to self: take the “Can games be art” discourse to the next level with “Is a given playthrough of a game art?”]

I don’t think this quite links into way elements of chance were used by dadaists. All my examples are more based around responding to randomness with the essentially the same toolbox as normal. responding to chance fairly rationally. Arp and other Dadaists were instead using randomness as a direct competator to rationality, challenging the idea that the world makes sense given the utter irrational monstrousness of World War I. I use randomness in my art as a starting point for a far more…I wanted to say rational but I think the word I’m actually looking for is “standard”. Maybe “normal”? “Boring” is probably too unfair to myself…a far more standard way. If I had to define my approach more firmly and possibly more fancily it would be that I use randomness to stimulate a world I need to respond to. It not only offers starting points for creation but limitations upon the work and upon myself, and that’s always been something I enjoy working with in art.

But.

We live in an age of easily accessible pseudo randomness. Whether that’s easily purchasable dice or electronic random number generators, it is very easy to rapidly create a whole selection of pseudo-random(truly random) numbers, and I want to explore what we can do with that, whether in text, in interactive fiction, in games, in music or in visual art. So that’s the next step here.

Things I want to read up on:

– Historical uses of randomness in art (including Dada’s)

– Other chance collages

– What contemporary artists are doing with randomness in different mediums

– How else is randomness used in our society?

– Difference between random and chaotic

– the physical nature of randomness.

Things I want to do:

– Create my own chance collages

– Create some basic code to start drawing random pictures with shapes and lines, and generate lots and lots of images using it.

– Create some basic code to randomly disort and rearrange photos

– Create a piece of writing that, while the main structure remains constant, each time you reload it certain details are randomised.

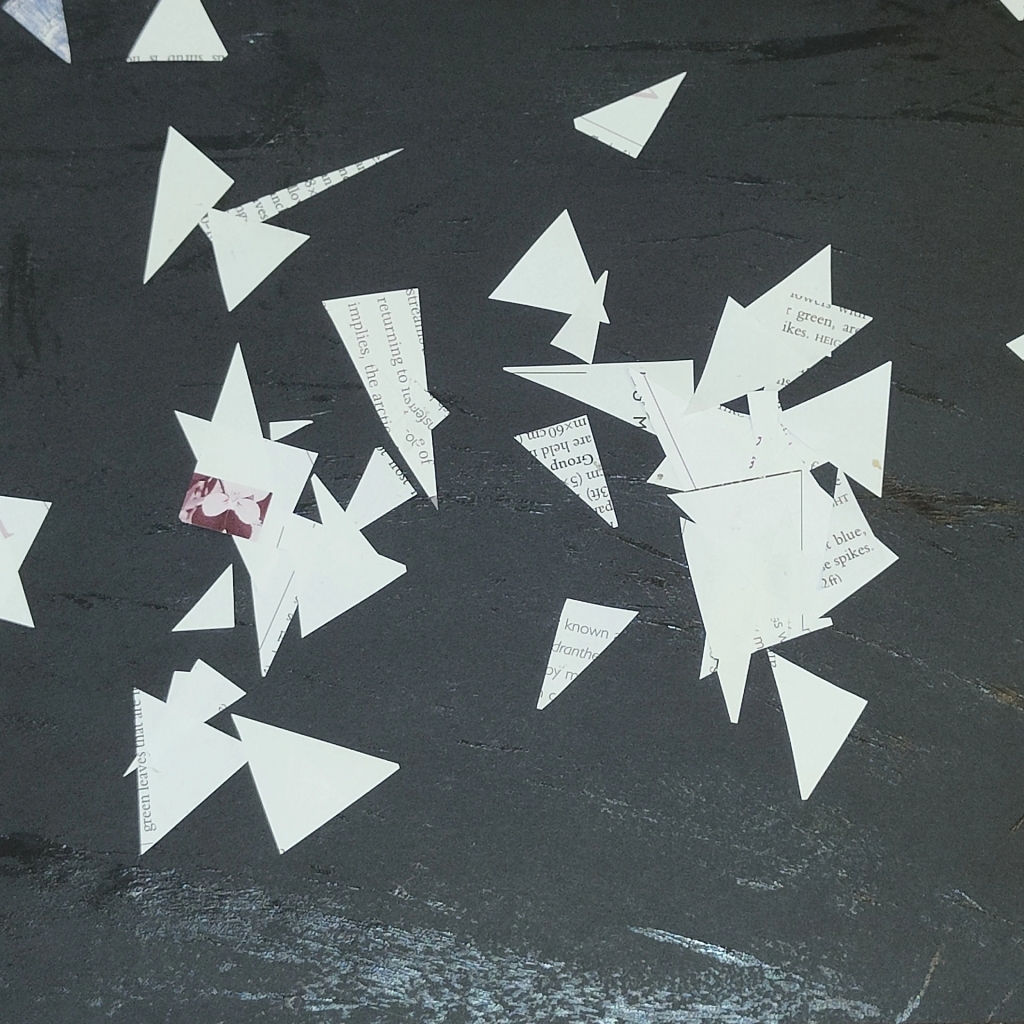

I’ve actually already done a chance collage. While I was trying to pack up my flat and therefore instead started stress collaging, I covered a piece of black card in glue and dropped a load of scrap triangles on it. The results of this are shown below. It isn’t a particularly catching piece, the glue gives a notable shine and I think I dumped probably too many triangles for it to really work, but doing it did help me nail down an issue I have with Arp’s work above. When I dropped the triangles, a.) they landed in many different orintations and b.) the actual distribution wasn’t at all uniform but instead, as I dropped them above roughly the centre of the paper, so most triangles landed lying on top of each other; weighted randomness is a thing. The squares arranged according to the laws of chance above are all orientated in roughly the same way, and are nice and spread out across the background, just don’t look random to me, despite knowing that many pople have made this accussation before and that Arp has said he geniunely did just drop the pieces. Maybe he did it repeatedly and chose the best one, since it is a posssible result for randomly dropping the ripped squares, but I still kind of find it unlikely. Maybe that’s unfair.

If you enjoy my posts and would like to support my work, please feel free to comment and share the links. If you would like to support me financially you can either join my patreon or buy my collages on society6.

7 Of Hearts: History in Bath Part 2 – Permanent Monuments and Temporary Exhibits in Bath Abbey (CW: Slavery)

Bath Abbey feels like graveyard folded up and over on itself into a church. Every stone you stand on is a memorial, dedicated to an honoured (read: military or wealthy) individual. When the floor was repaired and upgraded with better heating systems a few years ago, these stones were carefully removed, their exact position marked, and returned to their original resting place. Similar, if in better shape due to not being stood on, memorials line the walls of the Abbey up to just above my full height, meaning they tower over most visitors. These memorials are often personal, marble inscribed with the names and stories of those they remember, listing their virtues as persons. Often they didn’t live most of their life in the city of Bath but rather across the world, working in the united states (including a US senator), Africa, the Carribean, India…

It is easy to miss, as I did initially, that these memorials, dating from the seventeenth and eightheenth centuries, are often memorialising those directly involved in British colonialism, up to and including the capture, sale, purchase and torture of slaves. It is, for obvious reasons, rarely mentioned on the memorials. Except for when it is, with pride. One of the largest monuments is to William Baker, who was the director of the East India Company and later Governor of the Hudson Bay Company, two power private companies that helped establish the British Empire’s colonies in India and Canada, and who controlled vast amounts of the global trade network of the eigthteenth century. Above the plaque listing his life stands a carving showing a woman, representing London, obtaining resources from figures representing the various colonies.

Much like the Pitt Rivers museum, the Abbey is well aware of this history, and has been taking steps to address it. In the North transept stands the Monuments, Empire and Slavery exhibit. It was this exhibit that alerted me to the nature of the monuments in the church, and how, like so many institutions of the British Isles, the Church and the City of Bath profited massively from the colonialism of the British Empire and the slave trade it engaged in for many years, the Church of England outright owning plantations that used slave labour. The Abbey is, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, examining and making public this dark history of both the Abbey and those it memorialises. It is a good exhibition I think, particularly at the beginning, where it lays out very clearly the overarching history and issues it is confronting, and at the end, where it discusses what the Abbey is planning to do further and the organisations such as the Black in Bath Network and the Bath Ethnic Minority Senior Citizens Association that they are partnering with. There is a prayer, which I do understand is important for a Christian church, and it is acknowledged in the prayer itself that action must be taken to address this, as well as a poem, Dark Shadows, written by the local black poet Mark De Lisser a reading of which by the poet is avaliable here.

The middle of the exhibit is for me the weakest part of it, or at least the weakest part of the content, where it focuses more on specific stories involving the Abbey’s links to slavery, but it felt rather more…not outright apologetic, but pulled itself back a bit from its criticisms of them, describing how, for instance, a man hired as an explorer by the Royal Africa Company wrote in his personal log how he didn’t personally agree with slavery but he brought slaves at a market under orders of the RAC anyway. The poster ends on a line about how he viewed it as his duty, which just felt incomplete. In some ways it feels like the opposite of the musical Hamilton, which was happy to criticise Hamilton and his contemporaries on a personal level but struggles to criticise them on a political level, which explains the issues the musical has in approaching issues like slavery. Here, the exhibition is perfectly willing to make criticism on a political level, clearly laying out the moral failings of institutions, but seems to struggle with extending that criticism onto the people who made up those institutions, the people who’s memorials decorate the Abbey’s walls and floor. This issue of who’s stories are told in the exhibition extends the other way as well. While there are still discussions about enslaved people at the Abbey, including some who got baptised while they and the ones who currently enslaved them were visiting Bath, as far as I could tell and as far as I remember there weren’t any direct names or stories of the enslaved people given in the exhibit. Even in an exhibit discussing slavery and how we memoralise those involved in it, there were no stories of the enslaved.

That choice, whether due to unconcious bias or practical issues in the records the Abbey has historically kept (i.e. the evidence of the slave owners is far better perserved than the enslaved), is kind of a microcosm of a major issue with history. History is not the past. The past is far larger and includes everything, all the information lost to time, malice and apathy, all the people who’s story has, for whatever reason, not been told, but history is the stories we tell about the past, informed by the information that survives and reaches us in the present day and by our own biases and views. Every new examation of history, every narrative constructed in someway attempts to rewrite history, for better or for worse, and part of that is often establishing what information you think should be examined and what you think is important to leave for future historians when we become history ourselves.

And it is this, the information that is left behind and how it is preserved, that is probably my biggest issue with the exhibit. The monuments in the Abbey are old, centuries old, and are impossible to miss whether on the walls or beneath your feet. The stories as framed by those rich enough to have them carved into marble are a permanent part of the abbey, carefully replaced in the exact places they originally lay when the floor beneath them was modernised. The exhibition, for all the geniune good in it, is a temporary fixture, running till the fourth of september 2021, literally the day this blog post goes live. The posters are placed in a quiet corner of the Abbey, not as immediately eye catching as the monuments, and are on temporary wooden boards, not stone designed to last long after we are gone. It is a good step to make, and I wish Bath Abbey and its partners the best in their attempts to bring to light to these dark shadows, but I simply could not escape the contrast between wood and stone, paper and carvings.

If you enjoy my posts and would like to support my work, please feel free to comment and share the links. If you would like to support me financially you can either join my patreon or buy my collages on society6.

5 of Hearts: History In Bath Part 1 – A Morning In The Park

Like so many cities, the Bath is defined by its geography. Crossing several hills, the core of the city is the hot spring that still bubbles away today, producing millions of liters of water at temperatures of 46 degrees centigrade. Rainwater that fell on the hills thousands of years ago slowly drops through the rock below until it is heated enough by geothermal energy it is forced back up through a fault in the Earth’s crust. This spring is the only hot spring in the british isles, and it has been a major focus throughout human habitation here, and that has been a long time.

Bath is an old city. According to legend, as told by a sign near a statue of a man and his pig, the city was founded around a millenia before the arrival of the romans by a figure named Bladud, one of many individuals proclaimed at one time or another to be “The Rightful King of the Britons”, but was unable to take the throne due to contracting leprosy. Bladud was banished to become a swine herd, wandering the edge of the provience, where his pigs found a strange bath of hot water and mud. Upon bathing in it, the pigs’ various afflictions were miraclously cured, and so was Bladud’s when he followed their lead. In gratitude, after returning to the throne, he established a city around the healing springs, dedicated to the celtic goddess Sul. Later on the Romans arrived and called this place Aquias Sulis, a place sacred to the goddess Minerva, combined with Sul as Minerva Sulis. They build a complex combining a spa, what we might almost consider a health and leisure centre, and a temple, using the waters for worship, curses, health and pleasure at once. Once the romans have disappeared, the temple is built over with monestries and a new road plan, leaving the ruins untouched below the city for centuries. An Abbey is created where a king of England is crowned in a cermony that becomes the blueprint for all future corinations of English royals. The city starts as a royalist stronghold in the city The georgians return the focus of the town to a spa, the rich of that era flocking to the waters and the city to both heal and entertain themselves. The astronomer siblings William and Caroline Herschel lived and observed in the town. There is a museum in what once their house, but I didn’t have time to visit them, or the botanical garden further out of the city.

I found the story of Bladud on a sign in the city’s Parade Gardens, a waterside green space by the side of the river Avon, overlooking the Georgian era Pulteney Bridge and a v shaped weir built in the 1970s. The park, unusually, charges to enter the well maintained space: another sign explains that it was a private park for people living in the expensive nearby road, but a deal made years ago allows for public access as long as the council charges a small sum for upkeep. It is a very nice park, and for a single visit £2 is not bad, but it would be a lot if you lived nearby and used the space regularly like I do with my own local park. The gardens are below the level of the modern streets, the parades they are named for, and a private stair case still stands opposite to the public entrance I came in by. Another sign explains the history of the round band stand, decorated with musical notes, that stands in the middle of a lawn that was once a bowling green. Another details how this space was once outside the city walls, under the ownership of the first abbey of Bath, with a very small ruined wall left standing here that was once the Abbey’s mill. There is huge wall plaque detailing all the rewards Bath has won for the aesthetics of its city centre, like Britian in Bloom. The flowerbeds in the gardens are indeed impressive. To the right of the stairs leading up to the plaque are the public toilets, which charge 20p each, an issue in a post covid world where we have been encouraged to pay by card for so long I rarely carry physical cash. One of the flushes doesn’t work.

There is also a giant wooden slug big enough to be sat on, which isn’t really relevant. There are also photographs of an exhibit that once stood in the gardens, a trio of bears made from flowers grown, I assume, on a metal frame, surrounded by disapproving looking men in a style of dress I am unable to place other than “in the past”. I am both disappointed and very grateful these bears were not still here: it would be fun to see, but their eyes are hauntingly creepy just in these photographs and I am a crybaby who can write and GM horror but not experience it myself. Instead there stands a Armilary Sphere Sundial, with a note the time given on the sundial will need to be corrected depending on the time of year. I know I once knew exactly how to explain the plot it gives to explain the correction, but I have forgotten it now. It was cloudy anyway, so the sundial didn’t work.

Looking up from the gardens is like looking up at a collaged skyline, with buildings cut from history. The modern, the georgian and the medivial intermix and layer upon each other, and I already know there is more here, more history that I just cannot see while standing where I am.

For lunch, we go up to Pulteney Bridge, which is not just a road bridge but a whole street, with shops and cafes down the side. From the gardens it looked like the road was covered, but this was simply a strange optical illusion with the roofs of the buildings lining the side. The shops are varied and often specialist. One sells handmade masks and kits to make roman style mosaics, which I thought about but did not buy (although I did make a note to do some mosaic style collages), which shared a door with a shop buying and selling rare coins, while across the road is a shop that seems to only sell merchandise for the Bath Rugby team. Further down, a sign in the window of another shop proclaims that they only buy and sell geniune antique maps and that they do not sell reproductions: I look at the prices in the window on the old maps and wince. Finally we reach the end of the bridge, and find A.H.Hale Ltd, a pharmacy established in 1826, which, like so much here, wears its history on its sleeve, the window spilt between advertising for modern drugs and showing old pharmacy equipment and products once sold, a hand operated pill making machine next to a box declaring the wonderful hair brush inside made of that most magical material, plastic. We look at the houses beyond, and while there is something vaguely interesting looking at the end of the street, hunger instead proritises wandering back across the bridge this time looking at the cafes avaliable, not the shops. We find a pleasant cafe selling decent sandwiches and sit down, planning to visit two more locations in the afternoon. The Abbey and the remains of the roman baths.

Throughout this trip, and throughout other trips I’m going on with my family this week, I am making notes in a notebook and thinking about how I can put this together, both for my own sake, remembering the information I’ve learnt and the experiences I’ve had on the trip, but also thinking about how I can use this to create new things, whether taking reference photos for a collage or pulling all the notes together into a blog post like this, both for the sake of creating and to produce content for the internet.

History is not my field. I am interested in it, both the history of things I am otherwise invested in from mathematics to atmospheric science to Pokemon, and how history is used to tell stories about ourselves here and now, both on a personal and a political level, but I feel I need to establish now, during this slightly rambly introductory post to these three posts inspired by my visit to historical places in Bath that I am not speaking as an expert. Still, I hope I bring up some interesting points.

If you enjoy my posts and would like to support my work, please feel free to comment and share the links. If you would like to support me financially you can either join my patreon or buy my collages on society6.

7 of Hearts: A Visit to the Oxford Natural History and Pitt Rivers Museums

I’ve recently temporarily moved back in with my parents in my home town of Oxford, England, while I sort out obtaining some form of income and finding a new place of my own. It is a rather strange experience, both in terms of adapting to no longer living on my own and just returning to old haunts and the streets I remember from my childhood. Oxford is a small city and very much built to encourage cycling, including to places that I mentally have always classified as being too far to cycle: Boars Hill and Shotover Hill, both just outside the town, are places that as a child I always visited by car, not by bike, but they are well in cycling distance for me now as an adult. Moving closer in, the city centre is a bizarre mixture of stasis and decay; the colleges and the libraries, all the buildings that give the city the moniker “City of Dreaming Spires” remain, surrounded by closed down shops, driven out of business by a combination of the pandemic and lockdowns and the incredibly high cost of land around Oxford, both driving up the shop’s rent and limiting the number of people who can afford to live and work here. Oxford, with its incredibly high house prices and turnover in vital jobs like teachers and medical staff, feels rather like a zombie city; still very much alive, but very much dying.

That’s a discussion for another post though, because today, in the torrential rain, I hopped on a bus and headed towards one of those dreaming spires: the Oxford Museum of Natural History, and the Pitt Rivers museum attached to it.

Beginning construction in 1855 to house the new natural philosophy and science departments established in 1850, the museum is, even before you enter, an incredibly striking building, deliberately so. A lot of effort was put into the aesthetic of the building, both inside and out. With the central tower, long wings and the neo-gothic architecture it appears as a secular church, and indeed the construction was partially funded by the sale of bibles. Given that one of the most famous events to occur in the museum was the debate between Thomas Huxley and the Bishop of Oxford on evolution verses creationism. this appearance makes me giggle somewhat.

Having been a nerdy child who grew up in Oxford, the Museum of Natural History (or, as we usually call it, the Dinosaur Museum) is a place of fond memories. Following the trail of casts of Megalosaurus (the first dinosaur to ever be described) across the museum lawn, the anticipation of the short, shadowy antechamber as you enter, the charismatic megafauna of the central collection of fossils, which have stood there mostly unchanged for as long as I remember, with the iguanodon and tyrannosaurus rex casts greeting me like old friends directly ahead of the entrance doors, not quite as imposing as I remember, but still grand and impressive. The museum is incredibly light, with the main public area being enclosed by a glass ceiling, held upright by thin iron work pillars, with images of flowers and foliage incorporated into them. Around the edges, separated from the centre with pillars each made from a different type of rock run cloisters with specimen tables to one side and glass cabinets leading you through the geological eras of earth on the outside (as well as the mandatory somewhat overpriced museum shop). Another layer of cloisters is upstairs, giving fantastic views of the central covered courtyard and the architecture of the museum.

Indeed, in this new visit, it was mostly the architecture that really got my attention, rather than any specific exhibit on this visit. I wasn’t in a super detail orientated mood, preferring to just wander around and enjoy the cool space. In a neat piece of serendipity, the museum had a presentation about itself among the mammal skeletons, explaining its history and its design, letting me fill in gaps I sort of already knew from years of visiting it. That wandering established something for me: The Oxford Museum of Natural History is one of my favourite spaces to visit, architecturally speaking.

It was the thin iron support pillars that really caught my attention here. With the arches they make as they reach the roof standing in the aisles of the museum feels like standing in the ribcage of some vast, ancient animal which has swallowed me along with the elephants, dinosaurs and whales who’s bones stand here. It is a place meaningful for me as one of the first places I was allowed to really explore by myself, feet meeting the stones at my own pace, something that I find psychologically really important. It is precious to me as a place of learning, a place of exploration, a place of history both personal and natural, and as a place in and of itself.

However, there is one place within it I never went as a child. Through a pair of doors in the outer wall, you drop down a few stairs and find yourself in the main room of the neighbouring Pitt Rivers museum. The Pitt Rivers is a museum of anthropology, built around the collection of Augustus Pitt-Rivers, a Victorian scientist and military officer, with all the baggage that that sentence implies. The collection is housed in many, many, many cabinets of dark wood crammed throughout the room, dominated by a huge faded totem pole, taken from a Haida community, originally created, according to the A4 piece of paper sitting at the bottom, to celebrate the adoption of a young girl. It is an absolutely huge collection of artefacts from across the globe, including, for many years, a number of shrunk heads which have now been removed from view. The space feels small due to all the cabinets and pieces jammed inside, and the dark wood and opaque ceiling contrasts dramatically with the airy light of the Natural History Museum you’ve just left. Even before we talk about the colonial history of the collection or the curious way it is laid out, simply the physical space feels oppressive. I never went into the Pitt Rivers as a child not because I was scared of anything in there, but I was geniunely unsettled by just the aesthetics of the museum itself. It feels like If the Natural History Museum’s bone-like architecture matches its exhibits, then the Pitt Rivers matches its name in that it feels like you are standing in a pit.

The collection itself is organised not by time or location or cultural origin of the items on display but rather it is organised by what the objects are and how they are used. Japanese noh masks are next to masks from the African savannah and native american ritual masks. Instruments from around the world sit like a ghostly orchestra in their pit organised into strings, woodwind, drums. Weaving and textiles line the left hand wall in their glass cases. The idea is to allow direct comparison between cultures and time periods with objects intended to fulfil the same function, and while it does sort of work (and I suspect someone with more relevant training and historical background would get a lot more out of it than me) With the size of the collection there will almost certainly be something here that interests you, although due to covid restrictions I only had a limited time window so I didn’t spend too long in this section…and I just really don’t like being there in that space.

I don’t, however, want to sell the current staff of the museum short. The Pitt Rivers museum has done a lot of work trying to decolonise their activities. Numerous pieces have been noted to have been returned to cultural owners, exhibits like the aforementioned shrunken heads which displayed human remains and which focused on displaying other cultures as savage have been removed, and most visibly in the museum itself is a meta analysis of the museum itself, directly discussing the different ways colonialism expresses itself. Some exhibits have next to them annotated examples of how the museum used to label them, discussing how even in something as seemingly “objective” as a description, cultural assumptions and colonialism still slip through. Again, this is very much not my field: there is a reason that most of this post has focused on the feelings that the basic architecture, lighting and layout of the museum inspires in me, rather than deep discussions of the content of the museum. I have no experience in any of this, only what I’ve read around the issue since getting back this afternoon, but as far as I can tell from various articles, such as this one on Maasai tribal elders visiting the museum to assess and attempt to reclaim objects from the Guardian (which also raises the simple issue that a lot of the Victorians who collected this stuff in the first place just didn’t actually know what they were picking up, so there’s plenty of mislabelled objects in the collection), this one from the Uncomfortable Oxford organisation, a group dedicated to examining, as the name implies, the less comfortable aspects of the city and university’s history, and this post from Returning Heritage.. The consensus seems to be that the Pitt Rivers is doing a lot more than most museums to face up to and overcome its colonial past, with the two “but”s of a.) there is still plenty of other issues, such as legal issues around returning artefacts, practical issues about who to return them to, and, let’s acknowledge it, issues within the museum itself and b.) the museum is incredibly rooted in the history of colonialism, down to even its name, so it will still take a huge decolonialism effort to overcome this. Still, I want to acknowledge the work the museum has done, and continues to do.

It is just a little hard to look at the totem pole, erected for the adoption of a girl into a family, and not feel it is drastically out of place in this dark room.

One of the ways the museum has been trying to improve is by inviting in a wider range of individuals and groups to contribute to the museum, and in a brightly lit side room to the main display area sits an exhibition of particular interest to me, as a nonbinary trans individual. “Beyond the Binary”, an exhibit on a variety of queer experiences from around the globe spilt into categories including indigenous identities, rituals and identity, objects of power (whether created by or claimed by the queer community) and representation from queer individuals. Like the rest of the museum, it is an extremely dense display of objects and text surrounding them, although a number of centrepieces are given more space to show themselves than in the main section. Three that physically stood out were a pair of pianos with personal history for queer musicians, a wall designed to look like the tiles of a public toilet which was a common location for queer people to leave messages and trade secrets via writing on the walls, which is replicated here with a set of markers left for visitors, and the central figure of the exhibition space, a telephone booth covered in trans supportive stickers, featuring inside a tv screen giving the history of the local trans sticker artists. One that particularly stood out to me was a display featuring intersexuality, explaining the violence done to intersex people, and that made note of the differences, allegiances and tensions between the non-binary and intersex communities.

It was, overall, an extremely well done exhibit in the most part, but I do worry that it is a bit too inside baseball as it were as a public installation. While I understood a lot of the cultural background of what was on display, I’m not sure how someone unconnected to the community at large would approach it. It definitely does some things right, such as providing a sign of common community terminology at the entrance (for example, noting that the word queer is seen as offensive by some community members but has in general been reclaimed, and how it can be used as a noun, verb and adjective depending on the situation). Then again, the focus of the exhibit does not seem to be on telling one story (a practice that the museum is, of course, trying to get away from), but as many different stories as it can, some that I wasn’t even able to see because the full text required the scanning of a QR code, which my phone often refuses to do so I only do it when needed.

And that was my visit to these two museums. As I said, I was in a somewhat non-detail orientated mood, so my takeaway ended up being more on the museums themselves than the exhibits. After a quick browse through the museum shop, being tempted by a book on the history of the natural history museum and how it was built until I winced at the price tag, I left the building into the cloudy but not rainy afternoon.

I then got annoyed with myself for not remembering to go check if the bee hive on the stairs (a glass hive with exits through the wall to the outside of the building, not one that just lets out bees onto the stairs) was still there, but, unable to re-enter due to the covid visiting restrictions, I headed home, and wondered what other Oxford museums I could visit, and possibly write about here.

Six of Hearts: I am wrong about The Road Less Travelled By.

Headcanons, readings of text that are either not necessarily supported by the text can be tricky things. In some ways, it is natural to build on what is there, to bring in our own knowledge and experiences to our readings of characters, themes or word choices. It is, however, important to remember the difference between our headcanons and the actual text, if only because when we talk to others, they will bring their own constructions to the text, their own headcanons.

In some cases, these readings go beyond merely unsupported and, whether due to misreading, forgetfulness or antagonism against the text (or, indeed, other people’s reading of the text) become actively contrary to what was written. That is the position I find myself in when dealing with the Robert Frost poem The Road Not Taken. Or, as it is often mistakenly named (and I have delibrately misnamed it in the title of this blog post) “The Road Less Travelled By”.

My specific misreading is, like a lot of misreadings of the text, based in the final stanza of the poem. Unlike a lot of misreadings of it however, it is based on, or rather diverges from, the first two lines of that stanza. My default reading of the poem, the one my brain brings to the front before I can conciously correct it, is that the famous final three lines are being said in the future, after the rest of the poem, a triumphant, if wrong, declaration that what made the difference is that the narrator took “the road less travelled by” in an attempt to bring meaning to an ultimately minor decision. Indeed, sometimes I almost convince myself that the decision is so meaningless that in fact the two roads lead to the same place, despite this being completely false and actively contridicted by the text!

I think this reading is almost entirely brought on as a reaction not to the poem itself so much as the most common misreading of it, the “triumphant declaration” I mentioned above, which only really uses the final three lines of the poem. “Two roads diverged in a wood and I-/I took the road less travelled by,/and that has made all the difference.”. Commonly, the last full stop is, when read aloud, converted to an exclaimination point, as done by Robin Williams in the film The Dead Poets Society. It is treated as a declaration of independence, that what really mattered is that the narrator took “their own path” and didn’t follow the crowd. But again, I think this common reading focused on these three lines, which we might actually call The Road Less Travelled By, a three line poem in itself given how it is often used, misses a lot of the poem.

The rest of the poem is at pains to establish that “the passing there/ had worn them really about the same” and “both that morning equally lay”. The narrarator is faced with two options in the wood that (I assume autumn, given that the wood has turned yellow and the leaves are lying there undisturbed) morning, and they are, crucially, as far as the narrator can tell, essentially the same. The second stanza is, I think, pretty indecisive, capturing the feeling of looking down two options and trying to determine which to take. It is not an informed choice, given that the undergrowth blocks the view of the final destination of either road. But a choice is made.

Even in the final verse, the narrator notes this. “I shall be saying this with a sigh/ some ages and ages hence”,before reaching those famous final lines. The narrator knows not only that this is not a choice made based on the observable facts, but also that time will remake the importance of this decision and recast it as being a well thought out and indeed noble choice, to take the road less travelled by. In other words, the narrator knows that in the future, they will convert this sorry autumn day where they took the path that may be slightly less walked along, and turn it into…well, the three line poem The Road Less Travelled By.

But that’s not to say that this choice is completely meaningless, and certainly not that my reading of it as a minor or even meaningless decision is correct, because of what I think may be the most important stanza of the poem; the penultimate one. “Oh, I kept the first for another day!/ Yet knowing how way leads on to way, /I doubted if I should ever come back.”. The two roads are, in fact, leading to seperate places, and like so much of life, you can’t remake this decision. While the choice was not made for any particular reason, and will be reimagined by the narrator in future so that the reasoning behind it was the important part, the choice is still made. The narrator will not stand in these woods again and be able to take the other road. The title even puts emphasis on the other road. The road more travelled by. The Road Not Taken.

I’ve been thinking about this poem because I am at a fairly important crossroads of my own life now, and I am feeling drawn towards a particular path, despite having tried my hardest to climb another, steeper, possibly more rewarding but definitely more brutal on me path. Perhaps I will keep going, perhaps I will turn onto a new road, but one thing is for sure: I will not stand in this yellow wood again, as long as I live. There will always be a Road Not Taken.

Seven of Hearts: Climate Change as a horror story.

I am not good at handling horror stories. Even the tension in Doctor Who is enough to get me jumping out of my seat and leaving the room, much to the annoyance of anyone I might be watching with. But the more I think about anthropogenic climate change, the more I think one of the best ways to frame it is, indeed, with horror. But what kind of horror story is it?

Perhaps it is a cosmic horror story, with the climate and how it is changing because of us filling in the role of Cthullu or Hastur or one of the other array of Gods and Entities and Old Ones with bizarre spelling. The climate is a system far larger than us, and terrifyingly complex: even with all our computational power and mathematical techniques, even with satellite observations and vast networks of telemetric robots diving and rising through the seas, we still have huge holes in our understanding of it. In this model, like cultists, we merely raised an ancient god from its slumber, and it neither knows we exist nor has the ability to care as it crushes us. It does not care about us; the changing precipitation systems are not deliberately bringing drought and floods to us out of malice, but just because the system is changing, and outside of the most physical influences we have on it, both macrolevel influences like the urban heat island and global influences like releasing stable, harmful gases into it like CFCs, the climate has no interest in us. We are just small things in a world of small things.

Furthermore, much like the “sanity” measures so beloved by so many Cthullu inspired game systems, studying the climate very much has a detrimental effect on climatologist’s sanity: depression and anxiety are common in the field, even on top of the normal crushing feeling of academia.

But I think this doesn’t quite work. For one thing, we have actually clawed understanding of the climate from it. We do not have all the answers, but we definitely have quite a few, and studies to understand more continue all the time. We’ve understood that pumping CO2 into the air would warm the planet since Arrhenius’ work in the 1890s, ideas that built off earlier work from Fourier and Tyndall on the infrared absorption capability of water vapour, carbon dioxide and other gases. Despite what some claim, global warming has been the climate’s predicted path since the 1960s. The climate is not utterly inscrutable, even if we need to work out what the effects of our own actions will be.

Then perhaps we should turn to a different, more human made, form of horror. Perhaps we should look at climate change as a child of humanity, a child we are desperately fleeing from. Perhaps we should be looking at it in terms of that classic story of a scientist’s creation turning against him; perhaps climate change is our version of Frankenstein’s monster.

Frankenstein created the monster and brought him to life, but upon seeing him move, fled and allowed him to stumble off into the world by himself. There are two particular bits of this metaphor I think fit here. Firstly, the monster is initially not an entity with moral responsibility in and of himself; he is like a new born, or indeed, like a carbon dioxide molecule. We cannot blame the CO2 itself in anyway but the most physical for the warming effect it has, that is just what CO2 does. It is the one who released it into the world who must take responsibility, whether Dr Frankenstein or…well, all of us. And like Frankenstein, many of those in the best position to take responsibility refuse to until it is too late. When confronted with the reality of climate change, governments and corporations choose to declare that responsibility for it should fall upon the individuals, with focus on personal carbon footprints over systematic changes. Companies such as Shell knew about the risks, and distributed internally their own versions of Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth, but outwardly put their efforts into preventing anyone doing anything about it. Now there’s more and more attempts to regain control, more and more attempts to mount an expedition into the Arctic to find and subdue our creation, but, as the recent G7 meeting showed, it is a dysfunctional expedition, with every member looking for how they can give up as little as possible and wanting to use it to still get ahead. Some of those in power deem the monster, or climate change, as nothing more than a cryptid, a non-existent being chased only by the foolish or those with some kind of agenda, such as Thatcher going from opening the Tyndall Climate Centre to later declaring climate change was a leftist plot to bring in government control.

But again, there’s a major problem, because Adam, as the creature names himself, is not simply an unthinking CO2 molecule, but a living, thinking creature. This is an issue with the cosmic horror analogy; so many cosmic horror stories presume that the things we don’t understand are intelligences in and of themselves. They both also move the focus of the horror from us, the ones who are causing the issues, to the climate itself which seems…unfair, to us and, as little as it matters to it, to the climate. Note I said unfair, not kind, to us.

So then, what other stories do we have? Maybe we should be looking at global warming as a far more simple form of spooky story – a haunting. Ghosts are often portrayed as not having control of their own actions, wandering through walls because they are still following the paths they did through life, before those walls were built. What’s more, hauntings are often generated by human activities; murder and neglect. Climate change is, in this model, simply the ghost of all that fuel we have burnt into the atmosphere, coming back to haunt us not from any inscrutable motivation or even an understandable one, but because that is just the only thing the ghosts, formed from an ectoplasm of CO2, can now do. Or perhaps we could look at Poe, and the tell tale beat of the old man’s heart beneath the floor boards; a tell tale beat that the police officers who appear at the end unable to hear the beating and only believing him when he tells them to rip open the floorboards to find the body, as the officials of our world failed to respond to the tell tale warming measurements until now.

Again, despite this being my favourite of the three metaphors, and understanding that no metaphor will be perfect, it hides that in many ways the climate is living. Not in the classical sense, mostly, but it is constantly changing and adapting, and indeed, oxygen and carbon dioxide are extremely linked to life itself. The climate is not a ghost. It is a vast, confusing physical system with thousands of feedbacks and forcing mechanisms, both in and out of our control, and that we do not currently understand fully, but that we do understand enough to know how we are messing it up.Perhaps the real horror stories were the climate papers I read along the way .

Jack of Diamonds: The Cluedo Weapons

A small selection of collages of weapons from the game Cluedo, each colour coded to a separate character who might wield them.

Note: The side stories attached to these contain descriptions of murder and in one case suicide, which is why I’ve put it below the read more. While they aren’t too graphic, if you don’t want to see these, there is a twitter thread with just the images here.

3 of Diamonds: Top 10 Pokemon who would make great clowns if turned into humans

No I don’t know why I wrote this. Let’s get started.

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.